What's Really Going On in the Arctic?

In 1996, at a meeting in Ottawa, Canada, the Arctic Council was created by a collective of eight Arctic States and a variety of indigenous peoples' organizations with the purpose to address Arctic issues and challenges of common concern, to build communication and trust among the interested parties, to establish an organizing body to advance an evolving agenda, and to create a forum for research, discussion, and decision-making for the Arctic region. Subsequently, additional meetings of this group have occurred under a rotating chairmanship; the United States assumed the Chair for 2015 through 2017 and the next official Council meeting will be held for the first time in the continental US in Portland, Maine, in the autumn of 2016.

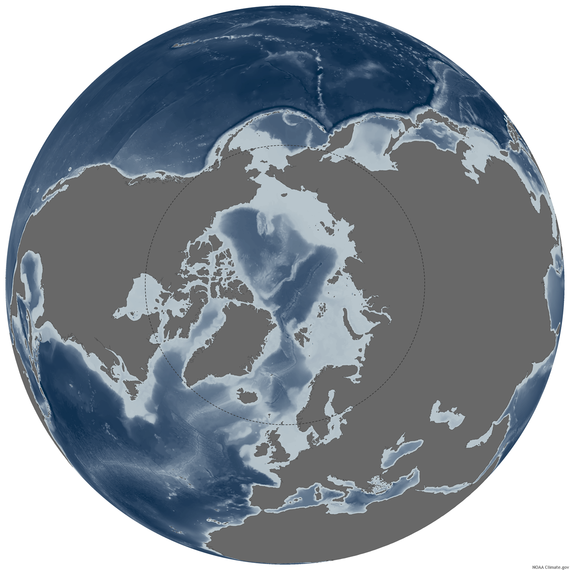

The goals of the Council are voiced by a commitment to a "peaceful Arctic" where issues can be resolved by cooperation and consensus and to the inhabitants of the region, their rights, social structures, cultural traditions, languages, and means of subsistence. Development is a second concern, which a statement issued in 2013 describes as follows: "The economic potential of the Arctic is enormous and its sustainable development is key to the region's resilience and prosperity... We will continue to work cooperatively to build self-sufficient, vibrant, and healthy Arctic communities for present and future generations." A third concern focuses on environmental and civil security, safety and response issues that may emerge from new and intensified activity. A fourth concern is health. "We are aware that the Arctic environment continues to be affected by events outside the region, in particular climate change...We are concerned with...the local and global impacts of large-scale melting of the Arctic snow, ice and permafrost. We will continue to take action to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and short-lived climate pollutants, and support action that enables adaptation." And finally, fifth, the role of knowledge is affirmed by supportive actions "to strengthen Arctic research and trans-disciplinary science, encourage cooperation between higher education institutions and society and synergies between traditional knowledge and science."

To advance these goals, a parallel organization was created, the Arctic Circle Assembly. Founded by the President of Iceland and held annually to bring together the many unofficial players whose work in research, policy, law, and specific areas of interest, the Assembly contributes to the discussion and definition of recommendations and responses that may be useful to the Arctic Council in its deliberations. I just returned from the Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik as a representative of the World Ocean Observatory. There were multiple presentations of the most recent national policy statements in preparation for the IFCCC Climate Summit in Paris in December and reports on progress in environmental law, fisheries research, shipping technology, and approaches to economic development. Everyone who claims a say was there - all the members of the Council, the observing states, engaged NGOs, and a spectrum of academics and scientists whose work contributes to the process. We heard from the U.S., United Kingdom, Scotland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Canada, the European Union, Germany, Norway, Japan, China, the Russian Federation, even Brazil - it was as if anyone who sensed opportunity in the Arctic had to be there to assert their mandate, declare their engagement, and present their plan or intention to be part in spite of the inclusive language of sustainability, consensus, collaboration, and cooperation.

Part of what, exactly? As a newcomer, I was struck by the focus on economic activity that underlay the high aspirations: oil and gas, shipping, and fisheries. Shell had just declared its withdrawal from Arctic drilling, thus the focus was more on gas and the LNG potential of the region. Mining was not overtly addressed, but it was mentioned in some break-out sessions with a long list of desirable ores and metals abundant within the region. Shipping, across the top of Russia and Europe, Canada and the United States, was excitedly addressed. Some 220 vessels transited the northeast passage during the recent three month ice-free season this year; there was much mention of the availability or lack of icebreakers to insure safe passage of flagged vessels. Fisheries was also seen as a situation that needed strict policies and regulations in order to protect the estimates of vast quantities of various marine species deemed to have move into Arctic waters as a result of over-fishing, sea temperature rise, and acidification in the high seas and coastal waters. The whole thing seemed like a coded conversation about the control of inevitable exploitation of Arctic resources, justified by high-minded agreement and theoretical application to the economic, social, and cultural needs of indigenous peoples referred to often but represented there in very few numbers. I departed beautiful Iceland confused. Something seemed not quite right.

What, really, was going on?

- Login to post comments

-