Culture, Connection and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

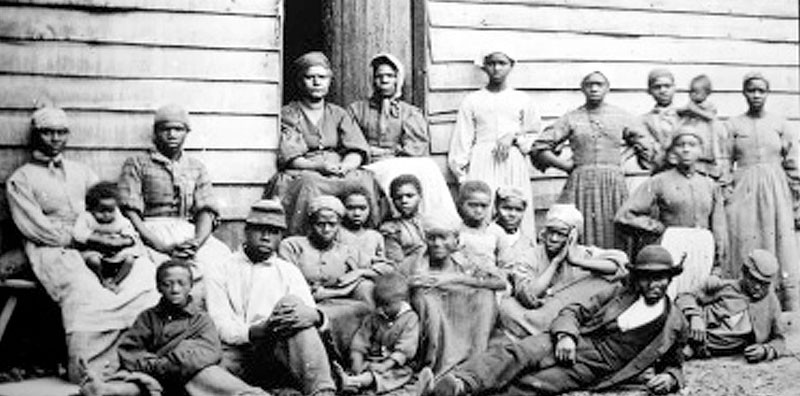

Africa Town, a community established by the survivors of Cotilda

Remains of what may be Cotilda, the last US slave ship, discovered in a muddy riverbank in Alabama. Image by Ben Raines, AL.comThere is but one ocean, that is perceived historically as a surface for exploration, transport, and trade — all factors in the making of civilization worldwide. But below that surface lies the detritus of the dangerous endeavor of voyaging, loss by storm, warfare, and ignorance of such a dynamic and challenging environment. The ocean has enabled connection for all time, and has built through the exchange of knowledge, skills, and traditions a vast contribution to world culture.

One of the most tragic illustrations of this process is trans-Atlantic slavery — the buying and selling of slaves from Africa to the west, South and North America primarily — as cheap, dispensable labor. In the United States, there are three major contributions to our cultural identity: the existing culture of native peoples living here for centuries; the ensuing European culture transferred through waves of immigration from England, Ireland, Scotland, and Asia; and the arrival of African culture through slaves that changed our nation’s patterns of settlement, music and language in powerful, undeniable, positive ways. Indigenous people, European people, African people — we are an amalgam of acculturation that lies at the heart of who we are.

Ballast blocks from the Saõ José slave ship, which sank in December of 1794 off the coast of South Africa. The Slave Wrecks Project

We must never allow that fact, and those memories, to be lost, and to guard against such forgetfulness, we turn to material culture — the objects, sites, and other evidence of such history as our foremost tool for preservation. That commitment, evinced by museums, libraries, archives, cultural sites, and national and international organizations such as UNESCO, is an essential part of an endeavor to conserve and honor this collective past is all its forms and manifestations.

Recently, as reported in the Smithsonian Magazine online news, the remains of what is purported to be the last ship to transport African slaves to the United States was revealed following the effect of a powerful east coast storm and flood conditions in a muddy riverbank near Mobile, Alabama. Researchers claim that the ship may well be the Clotilda, built in the 1850s as a transport for supplies from Cuba, purchased by a local businessman, and, commissioned to purchase 110 slaves in Ouimah, a port town in the present-day African nation of Benin. While slavery was then legal in the state of Alabama, it was in violation of US federal law outlawing the slave trade some 52 years before. If the vessel is indeed Clotilda, it represents an end, the last shipment of slaves. But it represents also a beginning: the survivors of that ship reported to have formed a nearby community, called Africa Town, in the middle of the American deep south on the verge of the Civil War.

At the 2017 opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, as again reported by the Smithsonian, artifacts from another slave ship, the São José-Paquete de Africa, a Portuguese ship wrecked of the coast of Cape Town, South Africa, in 1794 en route to Brazil from Mozambique carrying 400 slaves, were displayed as unique remnants memorializing the maritime aspect of the slave trade, an iron ingot used as ballast and a pulley block, recovered from a 200 year old ship and characterized “as thought to be the first objects ever recovered from a ship wrecked by transporting enslaved people.” The objects were on 10-year loan to the museum and their conservation had been partially funded by the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation, a program of the Cultural Affairs Office of the US Department of State. The grant of $500,000 had been designated in 2016 by the American Ambassador through the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs as recognition of the importance of these artifacts as symbols of the unifying cultural relationship inherent in the vast interconnected history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The US Department of State Facebook page related to the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation has today this statement: “Due to the lapse in appropriations, this Facebook page will not be updated regularly.” That cannot be. Memory cannot be truncated by budget cuts or ideological dis-appropriation. The implications of acculturation cannot be, like the power of an ocean storm, denied. There is wreckage there, disconnection. Real, sad, and final.

---

PETER NEILL is founder and director of the W2O and is author of The Once and Future Ocean: Notes Toward a New Hydraulic Society. He is also the host of World Ocean Radio, the weekly podcast addressing ocean issues, upon which this blog is inspired.

- Login to post comments

-